Chronically Ill, Chronically Overdressed

On health, gender, and getting dressed for the day

If you have noticed a recent increase in right-wing anti psychiatry discourse, you are not alone – it seems like everyone online has something to say about the mental/physical health of Gen Z, especially as it relates to an essentialized, traditional view of womanhood. I will be releasing a more critical essay on this soon, but I first want to reflect on my own experience, especially as an ill, femme person existing in the online fashion world. (For those seeking lighter fare, I will also have an interview coming out soon with the wonderful Jess Bosnjak, an illustrator and fashion creator from Ontario.)

When people ask what sparked my interest in fashion, I struggle to answer authentically – it is a deceptively complicated question. They might expect me to list my style inspirations or express long-standing desire for a creative outlet, or perhaps they are looking for something more personal, an experience I had as a child or teen. Despite its mundanity, getting dressed is a highly personal, weighted activity that shows up everywhere: in mid-aughts makeover scenes and opening montages, creating (and satirizing) portraits of the supposed routines of womanhood; in condensed, laid back, six-second clips by influencers on Tiktok and Instagram reels (I’ve made them, too); and in the DSM as one of the basic activities of daily living (BADLs), forming expectations around “normal” functioning and independence. During the worst of my health issues, it was difficult to get dressed without obsessing over whether I was signaling my ability to function – did I look clean or presentable enough to appear well? Did I look well enough to appear feminine? I feel connected to many different parts of myself while experimenting with my personal style, but above all else, my love for (and frustration with) fashion has been shaped by my chronic illness.

When I was first diagnosed in high school, I had very few places to go. I quit nearly all extracurricular activities and spent much of my time in bed, so I started passing time by putting outfits together on my bedroom floor. It was a hobby to engage with from my room, and it gave my body something to do besides feeling sad and ill – rather than thinking of my body as an adversary, a thing that was hurting me, I came to view it as something I could co-opt into working with me. In Illness as Metaphor (1977), Susan Sontag writes that some illnesses tend to render the body both literally and figuratively transparent through medical processes and discourse (12). In response to the overwhelming sense of exposure and transparency I felt by making my condition visible to friends, teachers, and medical professionals, I hoped to control my own opacity by mastering one BADL that could obscure my internal condition: getting dressed. This process of “obscuring” often simply meant outwardly conforming to normative standards of health and femininity. Performing a kind of “functioning” femininity helped me feel normal, at least in one sense, particularly when my pre-existing executive dysfunction was exacerbated by persistent brain fog. Dressing down, of course, is viewed as both unfeminine and unwell, a way of “giving up” on both gender and health. Even when I felt terrible, I knew that looking composed would make me seem better than I was. Looking clean and put together is a moralized ideal, especially for femme-presenting people – there is particular attention to the ways women get dressed and show up in their personal lives, so failing to do so feels like a gender transgression.

At the same time, illness has also been rhetorically co-opted to reinforce patriarchal gender norms. Tuberculosis offers the most obvious example of this process. Sontag writes that by the mid-eighteenth century, TB was highly romanticized and used as one way to signal “being genteel, delicate,” and “sensitive” within English high society (28). She notes that with the shifting class system, worth and station were asserted through both “new notions about clothes (‘fashion’)” and “new attitudes toward illness,” with “clothes (the outer garment of the body) and illness (a kind of interior decor of the body)” becoming “tropes for new attitudes toward the self” (Sontag 28). Though some of these ideas have shifted since their inception, I find myself conflicted, disoriented within time – does my illness make me seem weaker, softer, closer to a conservative, traditional ideal of a woman?

As Laura Hirshbein points out in her monograph on the rhetorical history of depression, American Melancholy (2014), explicitly gendered rhetoric around illness was integral to late-nineteenth century healthcare. She writes that physicians such as H.A. Tomlinson warned that American women were “in grave danger from insanity because they were ‘warring against their natural position’ of bearing children and attempting to avoid responsibility through their grasping for ‘material advancement or social opportunity’” (77). For Tomlinson, illness was a consequence of straying from one’s biological destiny. By 1906, however, research emerged constructing hysteria as an essentialized, female disease – an idea which transformed into the assumption that depression primarily affected women (Hirshbein 79). Though gender roles remain far from static, the medical industrial complex still seems to hold both of these contradictory assumptions: that deviating from essentialized womanhood is what makes you sick, but also that sickness is a biologically-destined quality of womanhood.

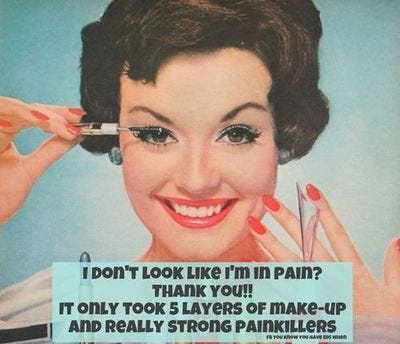

To cultivate a relationship with economically and environmentally sustainable fashion is to cultivate a relationship with the past through secondhand garments and, by extension, the older representations of gender reflected in each vintage seam or pleat. I gravitated towards the flowy blouses and looser skirts of the 50s-70s, choosing comfort that would still be deemed intentional. While fashion and comfort are major discussion points in chronically ill circles, their relationship with gender norms typically remains implicit. In the sixth chapter of The Rhetoric of Health and Medicine As/Is (2020), Sarah Ann Singer and Jordynn Jack examine characterizations of chronic illness on Pinterest. They outline four main repeating motifs in the memes, art, and photographs: “1950s housewives, spoons, cats, and bodies that make invisible ailments visible” (132). Their description of one particular image stood out to me:

In it, a 1950s-era woman wearing a full face of makeup, complete with red lipstick and matching manicured nails, applies mascara as she smiles at the viewer. The text reads: “I don’t look like I’m in pain? Thank you!! It only took 5 layers of makeup and really strong painkillers.” (134)

The fashion of the 1950s housewife is considered quintessentially feminine – so much so that her image is often taken up for reactionary ends – yet her appearance here draws attention to the process of getting ready, of walking through the BADLs necessary to construct the classic image of mid-century femininity. Singer and Jack suggest that the housewife’s invocation might represent “the masterful ability to conceal pain beneath a smile and polished appearance — even if it takes powerful drugs to do so” in addition to the “struggle with the expectations that women, in particular, should always look good, maintain a neat and tidy home, and put a hot meal on the table for dinner, all with a cheerful smile” (134). My illness has made this struggle a familiar one. Like my own experience, however, I think the housewife meme also captures another layer of complication: crucially, performed femininity is what allows her to mask her unidentified physical or emotional discomfort. The “5 layers of makeup” and “strong painkillers” work together, illness and gender performance each reinforcing the other.

Clothes and makeup did more than mask illness and pain; they also provided metaphors for more drastic medical interventions, attempts to discipline wayward female minds and bodies. In American Lobotomy (2015), Jennell Johnson references the rhetorical construction of clothing as a domesticating force within pro-lobotomy articles, stating that “lobotomy had the power to clothe naked women” (56). Though press accounts were divided, Johnson also references a prominent article that “claimed lobotomy helped women to fulfill proper adult gender roles” (58). Similarly, Jonathan Metzl’s Prozac On the Couch (2003) analyzes advertisements for late-twentieth-century psychotropic medication. Metzl notes that even between 1997-2002, Effexor advertisements featured “ringed women” smiling next to text proclaiming “I Got My Mommy Back,” “I Got My Marriage Back,” and “I Got My Playfulness Back” (155).

Like their earliest counterparts, these advertisements frame possible patients as wives and mothers, centering their social and domestic responsibilities and relationships. I see this rhetoric echoed in my own life – well-meaning people have expressed more concern over my illness than my queerness or neurodivergence in discussions around me finding a partner or having children.

I am frustrated by the way illness and gender transgressions have been intertwined by pharmaceutical marketing, but I am even more frustrated by the way right-wing writers flip these talking points for their own moral panics around mental health more broadly. The example ads I have discussed show how pharmaceutical companies marketed medication as a way for women to achieve traditional, conservative gender norms and step back into essentialized familial roles. Now, conservatives are moving in the opposite direction, creating a portrait of womanhood that requires being “natural” and unmedicated. Instead of being open with their anti psychiatry stances, however, they often cite rising numbers of mentally ill girls (on the left), discuss the glamorization of illness (on the left), and conclude that we are witnessing a culture of victimhood as a result of over-pathologization (on the left), all the while insisting that they believe many people do have the illnesses they claim to. I want to push back on this, because when you’re already in pain, it’s highly aggravating to hear people “debate” over whether that pain is rational, reasonable, or just a passing fashion we’ll all overcome, even if such points end with a vague concession that some people are probably telling the truth. It’s even more aggravating when people see my fashionable self-presentation and assume that I will validate their contempt for those who are unable to perform the same outward semblance of functioning.

The question I always want to ask is why, if they really are so against pathologizing and medicating disorders, these individuals wouldn’t then advocate for a more accepting, accommodating world that met people’s needs instead of demanding one rigid standard of functioning. When we put pressure on people to make it through the school or work day without accommodation, and medication (or even just therapy, which many people on the right also seem to take issue with) lessens the burden of doing so, it feels illogical to direct our anger towards those seeking treatment.

(Also, sorry for being slightly pedantic here, but many radical theorists in queer, mad, and disability studies also take issue with the way we pathologize disorders, so I’m tired of people insinuating that this is a thought the left doesn’t want you to hear. Nick Walker, for example, has proposed a distinction between the pathology paradigm and the neurodiversity paradigm; the former relies on “the assumption that there is one ‘right’ style of human neurocognitive functioning” rather than understanding our view of normalcy as socially and culturally constructed, while the latter views neurodiversity as its own form of diversity, moving away from the medical model’s framing of autism, for example, as a deficiency or disorder to cure. The difference between the right-wing thinkers and figures like Walker, of course, is that one group focuses on individual successes and failures in the context of existing standards of functioning, while the other refuses to view those standards as sacrosanct, instead asking us to imagine and work towards creating a more accessible world.)

I understand that we might not understand the reasons holding someone back, or we might view their reasons as irrational. At the same time, pain is irrational, and the “wrong” reasons shouldn’t make someone undeserving of structural support. If we accept that people around us really are ill, then we must also accept that concepts like pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, returning to “normalcy,” and beating the odds are all relative. I remember a time when just going to class was cause for celebration; my tenth grade teacher called me “wonder girl” for simply meeting my accommodated workload. I can do far more today than I could then, but my body is still unpredictable. Not everyone has the energy to mask their pain, and when it really comes down to it, these anti medication panic pieces seem deeply uncomfortable with witnessing pain at all – whether it comes from a medicated or unmedicated person. I truly hope I won’t be in pain forever. But while I am, where should I go? Regardless of how stoic I am, how much I force myself to do, how put together I look, I am still ill.

Illness, fashion, and essentialized portraits of femininity have long been intertwined, and I find that I sit uneasily in this long history of sick women. I feel at once deficient and in a state of biologically destined patriarchal conformity, infantilized or invisible unless I grasp for a gender I primarily relate to aesthetically. At the same time, I understand how I have come to feel this way – the gendered rhetoric around health and illness seems unstable, in a cacophonic state of constant flux and contradiction. If we want to build solidarity and care, we need to expand our own visions of what it looks like to function, moving beyond the conventional assumption of neurotypicality, able-bodiedness, whiteness, quiet femininity, or confident masculinity.

For now, I am exhausted by each new morning and nightly beauty routine framed on Tiktok as necessary cycles of girlhood. I am exhausted by the comments under these videos, which frequently say “I’m doing womanhood wrong.” I am exhausted by my own routine, which cuts into my sleep. I will always love fashion, but I am exhausted by getting dressed. I don’t want to co-opt my own body, to use it as a shield; I want to rest.

Works Cited

Hirshbein, Laura. American Melancholy, Rutgers UP, 2014.

Jack, Jordynn and Sarah Ann Singer. “Theorizing Chronicity: Rhetoric, Representation, and Identification, on Pinterest.” Rhetoric of Health and Medicine As/Is, edited by Jennell Johnson, Ohio State UP, 2020, pp. 125-142.

Johnson, Jennell. American Lobotomy, U of Michigan P, 2015.

Metzl, Jonathan. Prozac on the Couch, Duke UP, 2003.

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor, McGraw-Hill, 1977.

Getting dress being in the DSM as one of the basic activities of daily living is so interesting to think about! I so relate to feeling like getting dressed in the “right” way is so important for how people see me, like if I have one off day it will change dynamics. As much as I love fashion and style, it is a lot sometimes.

Such a rare topic, thank you for covering it and exploring in such depth. Everything makes sense. I, too, find all those beauty routines tiresome. I used to think I’m not doing it (being a female) right. I now understand that my brain type (with added ‘bonus’ of being born in a family I grew up with) just cannot — and refuses — to operate all that ‘femininity’ one is supposed to do in order to pass as a female in the society. I rather read books.