You’re reading Out is Out, a newsletter exploring the worlds of fashion, literature, and internet culture. Sign up below to send each new post to your inbox!

Last month, Vogue dropped this tweet, announcing the arrival of a new trend: “chocolate syrup hair.”

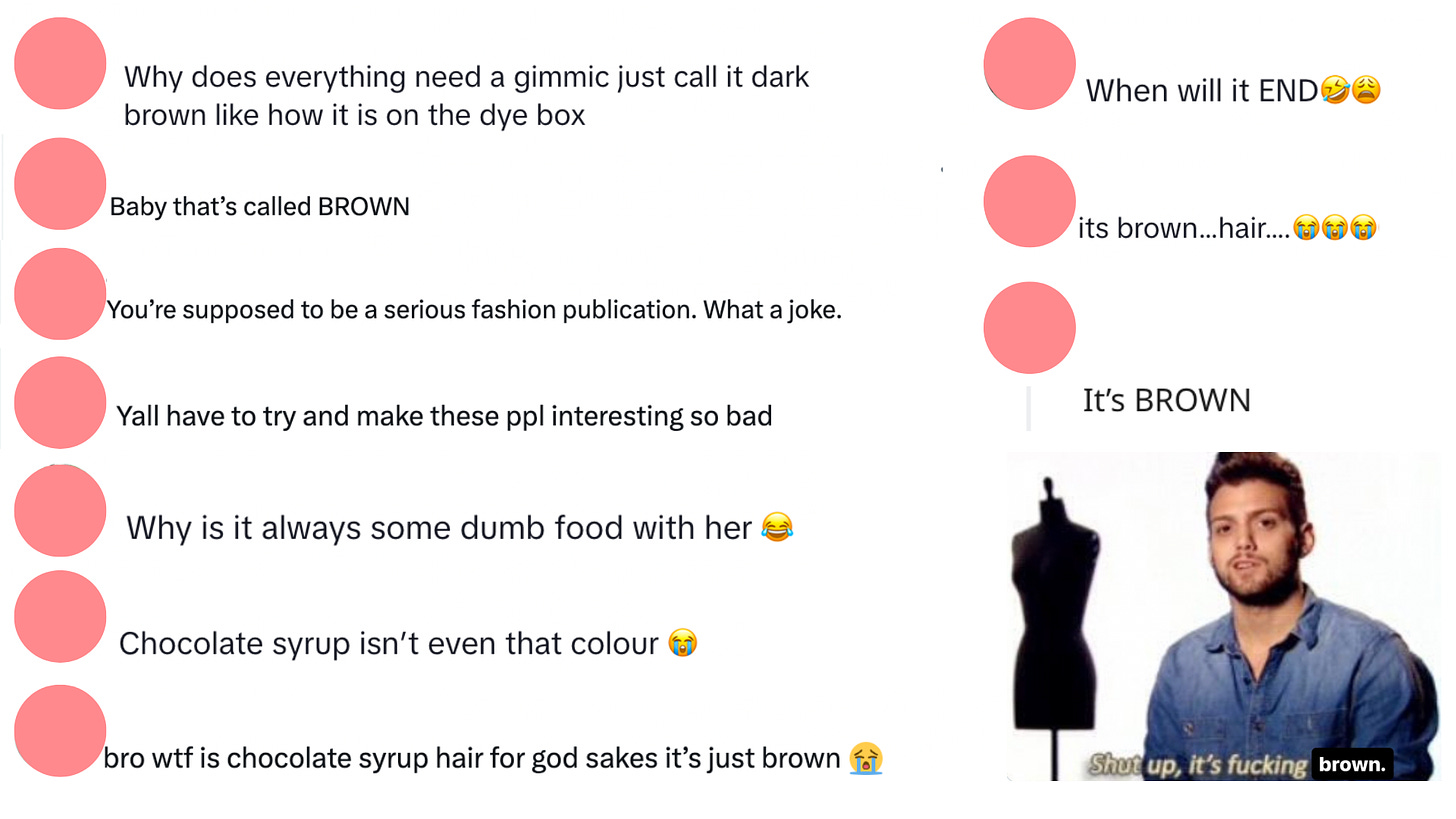

The internet reacted quickly. Twitter and Reddit were filled with snide comments about how people will turn anything into a microtrend, “chocolate syrup” is just a clumsy repackaging of brown, and that marketing teams are just trying too hard. As with many ridiculous pseudo-trends before this one, the smart, enlightened consumers joined hands in a grounding moment of peaceful solidarity to laugh at those silly interns, at the overeager influencers rushing to adopt each aesthetic, at the brands quickest to drop a curated collection based on new key words. But oh, fellow consumers, how do you know they weren’t laughing back at us?

Of course, I sympathize. I too shared this knee jerk reaction – as soon as I read the tweet, I rolled my eyes, annoyed by this pervasive style of marketing. The endless categorization of personalities, aesthetics, and even daily routines online has been exhausting to watch. (For my more offline readers, some of these personality/aesthetics have been named “tomato girl,” “vanilla girl,” “office siren,” “grandpa core,” “coastal grandmother,” or “clean girl,” and these archetypes might engage in activities like “bed rotting,” eating “girl dinner,” doing “girl math,” or creating “girl mess.” If this sounds strange and overwhelming to you, you are not alone.)

My initial response to the “chocolate syrup hair” tweet, however, felt too easy, especially after earlier (and eerily similar) controversies involving Vogue and Elle. For context, in 2022 and 2023, these publications helped push beauty terms like “glazed donut nails” and “brownie glazed lips” after Hailey Bieber was spotted sporting them. These trends sparked a whirlwind of think pieces and critical videos — many of which pointed out that each “new” style was merely a renamed version of something classic (opalescent top coats and brown lip liner with gloss have been around for ages, of course, with the latter being a staple in Black and Latina communities long before white celebrities attempted to co-opt and rebrand the style).

A similar cycle occurred with Sophia Richie’s “blueberry milk nails” (read: light blue nail polish). There is undoubtedly a strange desire to coin a term for everything online, and fashion journalists are certainly not immune to this compulsion. But if Vogue could make the same mistake a fourth time, how much of a mistake could it really have been?

Perhaps I’m just putting on my 60s Space Race-inspired tinfoil hat, but I don’t think it was a mistake at all. After all, people love to hate things, and this style of tweet seems like the perfect way to generate discourse – intentionally or otherwise. I’m beginning to realize that these simple, sensationalized trends win either way: either they make people mad, generating endless think pieces and dunk tweets about the ridiculousness of each idea, or they catch on, creating new trends. In either case, traffic is driven to the publication. It’s the perfect storm of discourse bait. And wow, the bait worked:

’s recent essay, “The Discourse Age,” provides a great overview of the current hellscape of online discourse. She aptly notes that:even given the fact that the most controversial figures will appear outsizedly popular in the internet sphere, most “discourse bait” happens in a one-off Tweet. It’s not always purposeful — usually when it is, most can spot the troll behavior and react accordingly — but for anyone who’s even the least bit digitally literate, you know where the hot buttons are and how to press them.

Eliza also points out that discourse bait posts — as opposed to overt troll posts and unambiguous rage bait — usually gain more traction, as people are “much more willing to have a conversation regarding an ambiguously prodding post than a straight-up hateful or vile one.” I think this is right, and it also describes how many fashion trends (or pseudo trends, perhaps) operate in the current state of social media: they are intentionally ambiguous, double-edged attempts to walk the line between outrage marketing and sincerity. In other words, they cater to both potential lovers and haters of each proposed trend. This is the trend bait trap.

The Vogue tweet is a great example of one such “ambiguously prodding post”: it pokes at current conversations around overcategorization and the rapidly increasing trend cycle while simultaneously launching a shiny, new tidbit of hair inspiration for consumers genuinely looking for change. The fact that the former category is now just as valuable as the latter within marketing is what interests me most.

The recently-coined “mob wife aesthetic” – which features fur coats, leopard print, and Italian leather bags – shows us something similar about the role of the hater in contemporary fashion discourse. Spearheaded primarily by kayla trivieri, this aesthetic first went viral on Tiktok with the declaration that the “clean girl” look – a fashion and beauty trend involving minimal makeup, clear skin, and sleek hair – was now out, while “mob wife” was in. Now that we have finished taxonomizing each archetype of girlhood, we can finally begin to categorize womanhood! #Win!

The original video received mixed responses. Some people were taken with this new aesthetic, while others found Trivieri’s assertion forced, given that it was not actually a trending style – just an attempt to generate one. Like Hailey Bieber’s chocolate syrup hair, the mob wife was thrown out for audiences to dissect and, eventually, inflate to trend-adjacent status as a result of passionate discourse.

This has occurred many times before, of course, largely due to the influx of professional and self-proclaimed trend forecasters online. Rachel Tashjian correctly suggests that:

On TikTok, trend forecasting has become the new influencer hustle, almost a trend itself; creators who can string together photographic evidence with a pithy and compelling monologue are performing a kind of competitive prophecy. And the platform’s algorithm seems to favor this sort of information sharing: the more ridiculous the prediction, the more traction it gains, and the more predictions we are fed.

As a result, it is becoming increasingly difficult to tell genuine trends from simulated or baselessly predicted ones.

of recently echoed theories about the mob wife aesthetic even being planted as a way to market the Sopranos 25th anniversary. Was this a clumsy attempt to force a trend, to try making “fetch” happen, or was the controversy anticipated from the start? Was this just a casual idea thrown out into the internet, only to be met with unanticipatedly strong opinions? In any of these cases, the marketing was successful: like many others, I might not have discovered the aesthetic or the Sopranos reboot without the controversy surrounding them. I think there is something more complicated going on than the simple adage that “all publicity is good publicity,” however – it’s as if haters have become a hot niche of their own, forming a joint target audience with the sincere consumer.Nothing captures this phenomenon better than current teen movies, which mastered this over the last ten years. A few years ago, I fell down a rabbit hole of Netflix Original teen rom-coms. I, alongside many others, hate-watched The Kissing Booth, Sierra Burgess is a Loser, Tall Girl, He’s All That, and any Noah Centineo movie I could get my hands on. Clips from these movies often went viral for their cheesy tropes, general absurdity, and cringey writing. The assumed target audiences of these films were adolescent girls interested in teen comedies, who generally seemed to rate them highly out of either sincere appreciation or a so-bad-it’s-good approach. “Enlightened” viewers like me, however, reveled in the perceived cringiness of these movies. I thought I was so smart, so cool for laughing at the writers’ incomprehensible missteps. No tragic hero has ever had such hubris as this.

Reviews for Tall Girl – one such widely mocked and memefied movie – typically fall into two camps: 1) sincere odes which take the movie at face value, applaud the execution of its basic message (love yourself as you are), and emphasize the benefits of showing it to insecure tweens and teens who might otherwise feel alone, and 2) passionate, multi-paragraph breakdowns of each hateable character, scene, and trope. Two common refrains, “what were the writers smoking?” and “how could they write something this stupid?” were echoed across Youtube, Tiktok, and Reddit. These critiques drew tens of millions of views, which in turn, of course, led to more streams of the movie. It generated enough buzz to justify making a sequel, and Tall Girl 2 was the single most popular movie on Netflix in the week of its release.

(Note: spoilers ahead for the end of Tall Girl, for those eager to find the light after hearing my tragic tale.)

Now, watching Tall Girl is what finally shattered my illusion of superiority. In one of the final scenes, Jodi Kreyman, the titular Girl, finally gets together with her guy best friend, Jack Dunkleman. Jack, a short nerd who carries everything around in a milk crate (instead of wearing a backpack or tote bag like the rest of us), makes his move: he stands on the aforementioned crate and kisses her, finally fulfilling her dream of being with a guy taller than her.

Chekhov’s milk crate sent me over the edge. It was undeniable: I had fallen for the bait.

I was a puppet, and the writers were pulling the strings; the sincere, appreciative adolescents and my band of haters were both targets from the start. It was a deeply humbling realization, and now when I see people boldly hating on media without hesitation, I feel that same nauseating foolishness gnawing at me. It’s easy to feel like hating is a subversive act, I think, especially when such hatred feels grounded in moral objections (as it often does). In Tall Girl, such objections frequently centred around her obvious privilege as a well-off, conventionally attractive white girl, which make her complaints about heightism particularly eye roll-inducing; with chocolate syrup hair, they typically focus on the sickening churn of overconsumption and microlabels under late capitalism. This is not to say that those critiques are wrong or unnecessary, but rather that these trends and pieces of media are designed to elicit them. It’s all part of the trap.

So: is “chocolate syrup hair” a marketing intern’s clumsy attempt at coining a term, or is it a disingenuous attempt to generate rage clicks and engagement at any cost? It’s both, baby!

Even so, what comes next? If we know that the trap is here, should we disengage? Critique its presence despite the engagement we’re giving them? Something else entirely? My own experience in marketing leaves me uncertain.

One thing I do know is this: even in the fashion world, it feels increasingly necessary to take each hot take or prediction with a grain of salt if you’re interested in developing your style (or preserving your peace of mind).

Those are my parting words. For now, I leave you with this, dear readers:

Works Cited

Mclamb, Eliza. “The Discourse Age.” words from eliza, 8 Jan. 2024, www.wordsfromeliza.com/p/the-discourse-age.

Odell, Amy. “The ‘Mob Wife’ Trend Is Fake.” Back Row, 28 Feb. 2024, amyodell.substack.com/p/the-mob-wife-trend-is-fake.

Tashjian, Rachel. “Real Fashion for the Era of Fake Trends.” Harper’s BAZAAR, 5 Apr. 2022, www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/fashion-week/a39631139/fear-of-god-eternal-jerry-lorenzo-interview.

Thank you so much for reading! I had originally planned for this post to be just 1000 words and far less goofy, but I really couldn’t restrain myself. Please let me know what you think of this format, and feel free to share other trend bait traps you may have fallen into…

What a lovely and well-articulated piece! I completely agree — these trends are getting outrageous! I always find it difficult to criticize these trends, partially because I worry that I’m just jumping on the bandwagon of hating women; I worry that my criticism will manifest into real misogyny. But all these trends do is illuminate the proliferation of capitalism and consumerism, and it’s a shame that “girlhood” becomes commodified.🫤 you’re so right though and I can’t wait to see what you write next!! ❤️❤️

This is exactly how I feel about the Cut piece (I Married an Older Man).