You’re reading Out is Out, a newsletter exploring the worlds of fashion, literature, and internet culture. Sign up below to send each new post to your inbox! As soon as an audio recording of this essay is available, it will also be available here.

In March of 2022, when I first began planning this newsletter, I drafted an outline for an essay titled “‘Out’ is Out: Tiktok and the Destruction of Trend Cycles.” Perhaps ironically, the original subtitle has now gone through many changes — the conversation around the rapid churn of consumption, microtrends, and the flattening of individual personal style on Tiktok has itself become a passing trend, with these observations now feeling commonplace and banal in online fashion discourse.

Though so much has changed in the last two years, this conversation has recently been revived, with Tiktok users like Elliot Duprey even referring to the current state of things as a “personal style epidemic.” As Duprey and many others have now pointed out, the recently-coined (and now-infamous) Eclectic Grandpa aesthetic, which mimics a lifetime of curation and experimentation, seems to perfectly embody our current confused, generally nostalgic cultural moment.

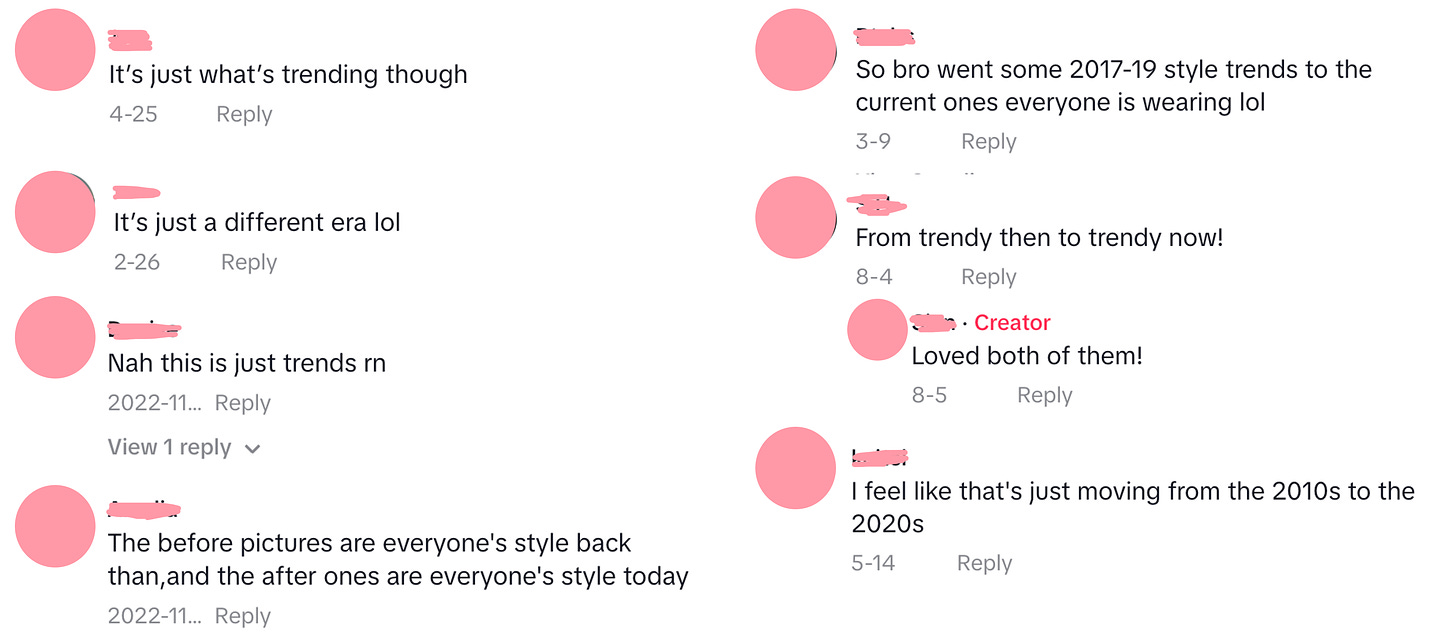

Yes, so much has changed about engaging with fashion online, but one thing has not: it is deceptively difficult to identify what is actually trending or on the rise. If you look at the comments alongside “style evolution” videos on Tiktok (including anything labeled “before vs. after finding my personal style” or “dressing for the male vs. female gaze”), you will likely see comments insisting that the outfits from both before and after are merely following the trends of their respective times. In addition to expressing intriguing resistance to anyone claiming true individuality online, these commenters also offer valuable insight to a compelling truth about the current state of fashion as influenced by the internet: with the ever-increasing number of online subcultures (or, perhaps, algorithm-driven corners which merely feel like subcultures), nothing is truly “out” anymore.

Some things are still in, of course, as they always will be; this was unmistakably the autumn of red accents, ballet flats, and bows, for example. What is out, however, is increasingly nebulous. The biggest trends of the last few years have been influenced by the 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and 2000s, and numerous forecasted trends for 2024 — including sailor-inspired fashion, which I will be releasing an essay on soon — simultaneously draw on the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 2010s. If the twentieth century has been turned into one big fashion bingo card, an Edwardian renaissance is the only thing blocking our total blackout.

In Fashion Trends (2021), Eundeok Kim, Ann Marie Fiore, Alice Payne, and Hyejeong Kim describe the traditional fashion life cycle, with which you might be familiar:

All products, including fashion products, have a finite life cycle. New styles are introduced in the market, last for a certain period of time, decline, and finally disappear. Although the rate and duration of use vary, the diffusion of a specific fashion tends to follow a predictable cycle, called a fashion cycle or fashion life-cycle curve.

On the internet, however, this cycle has been radically altered. In addition to gaining or losing relevance much faster, I find that trending styles also no longer feel finite; rather than disappearing and fading into the typical end-stage of obsolescence, they seem to linger in the background. It’s as if we are always slightly haunted.

This phenomenon is not solely confined to fashion, of course. Though shaped by the conflict over ownership of her master recordings, Taylor Swift’s re-released music and subsequent Eras Tour are great examples of how — as she puts it in “marjorie” — “what died didn’t stay dead.” With each (un)dead era, Swift’s model releases the past from behind us, reviving it for endless reconstruction and making it available for a new generation of consumers to experience for the first time.

(To be completely clear, this is not a critique of Taylor Swift’s choice to re-release her albums. I just think it’s fascinating how Swift’s current projects coincide with today’s broader interest in nostalgia. Whether intentionally or not, Swift has her finger on the pulse of something.)

This year’s Met Gala theme — “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion” (of which Tiktok is a lead sponsor, incidentally) — looks incredibly exciting, and it, too, encourages us to look back and revive styles from over 400 years of fashion history. Writing for Vogue, Luke Leitch shares that the gala will feature pieces ranging from “a 17th century English Elizabethan-era bodice to 21st century acquisitions by designers including Phillip Lim, Stella McCartney, and Connor Ives.” As the Met Costume Institute has been a curatorial department since 1959, historical references have always been staple features of Met Gala looks. 2021’s two-part theme, “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion”/“In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” was an explicit tribute to America’s fashion history, while other themes have paid tribute to specific periods, such as 2004’s “Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the 18th Century” or 1989’s “The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire.”

This year’s theme feels different than the gala’s typical approach to historical references, however. Like the hauntedness of current trends and Swiftian undead eras, the characterization of older fashion as something to “reawaken” implies a similar kind of slumber, a rejection of the in/out or alive/dead binary in favour of liminality or spectrality.

When asked about each theme’s decision process, Andrew Bolton, the Costume Institute’s chief curator, told Vogue France: “What I try to do is work on a topic that seems timely, and that defines a cultural shift that’s happening or is about to happen” (qtd. in Berlinger). Isn’t “Reawakening Fashion” the perfect theme for a world in which “out” is out — one in which past, present, and future eras appear indistinct?

As

points out in this Cafe Hysteria piece, our cultural understanding of taste is also increasingly complicated by widespread ironic appreciation for the tasteless, making some nostalgia-fuelled fashion trends even harder to identify. Cultural critics such as Franco Berardi, Mark Fisher, and Fredric Jameson have also written extensively on the role of nostalgia in other facets of current pop culture. For Fisher, there is something necessarily spectral or haunted about contemporary electronic music, for example, which fails to deliver “futuristic” sounds despite previously being synonymous with an aestheticized sense of the future. There is something similar, I think, about the current state of fashion, and I can’t wait to explore it with you.Thank you for being here! This is a taste of what I have planned, including a deeper dive into the idea of “out” is out. This newsletter will combine my love of fashion, literature, history, and cultural analysis to explore topics such as the culture of categorization on Tiktok, our obsession with eras, the concepts of online girlhood and “personal” style, what our consumption habits mean, the role of friction in shopping, general fashion inspiration, and how to “read” an outfit. Readers can expect one long(er)-form piece per month with smaller pieces interspersed between.

Above all else, I hope this will be a safe space for community and discussion — it’s so strange to have conversations across different mediums, and I hope Substack will help bridge the gap created by platforms like Tiktok and Instagram.

I am incredibly excited for Out is Out, and I can’t wait for you to join me.

Works Cited

Berlinger, Max. “How The Met Gala Theme is Decided Each Year,” Vogue France, March 5th, 2020. Accessed 1 January, 2024.

Buxbaum, Gerda. Icons of Fashion: The 20th Century, 1999

Fisher, Mark. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 1, 2012, pp. 16–24. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

Huizinga, Madison. “Is Having Good Taste Overrated?” Cafe Hysteria, 1 Oct. 2023, madisonhuizinga.substack.com/p/is-having-good-taste-overrated.

Kim, Eundeok, Ann Marie Fiore, Alice Payne, and Hyejeong Kim. Fashion Trends: Analysis and Forecasting. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021. Bloomsbury Collections.

Leitch, Luke. “‘Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion’ Is The Costume Institute’s Spring 2024 Exhibition,” Vogue, November 8, 2023. Accessed 31 December, 2023.

Siddiqui, Yusra. “Eclectic Grandpa Is the Controversial Trend That’s Already Defining 2024.” WhoWhatWearUK, 19 Jan. 2024, www.whowhatwear.com/uk/eclectic-grandpa-trend.

Loved this post! I was JUST thinking recently about how cheetah and/or leopard prints have historically gone in and out of fashion, but nowadays they seem to just be lingering around? I'm excited to see what attendees wear to the Met Gala this year!